UK Government decides on 'agile' AI regulation

Will a light-touch regulatory regime allow us to be more flexible or stop us from effectively protecting ourselves from the risks of increasingly powerful AI.

“The future of AI is safe AI. And by making the UK a global leader in safe AI, we will attract even more of the new jobs and investment that will come from this new wave of technology” - Rishi Sunak, the Prime Minister

The UK’s Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) has today released their ‘pro-innovation approach to AI regulation: government response.’ It is in response to August 2023’s ‘pro-innovation approach to AI regulation’ white policy paper produced by DSIT and the Office for AI.

The paper released today is important because it lays out exactly what the UK’s pro-business strategy on AI will be, how they will respond to the risks from increasingly capable models, and just what their ‘agile’ regulatory approach to AI will look like.

This blog will:

Go through the paper.

Assess the ‘agile’ regulatory proposals using legacy regulators instead of creating a new AI-focussed regulator.

Ask if such a light-touch regulatory regime effectively protects us from the risks of increasingly powerful AI.

Today’s Press Release

As per the paper’s accompanying press release today, the UK’s approach to AI regulation is to ‘ensure it can quickly adapt to emerging issues and avoid placing burdens on business which could stifle innovation.’

The UK believes that AI is ‘rapidly developing, and the risks […] are still not fully understood. The UK government will not rush to legislate, or risk implementing ‘quick-fix’ rules that would soon become outdated or ineffective. Instead, the government’s context-based approach means existing regulators are empowered to address AI risks in a targeted way.’

The Secretary of State for Science, Innovation, and Technology, Michelle Donelan, explains: ‘AI is moving fast, but we have shown that humans can move just as fast. By taking an agile, sector-specific approach, we have begun to grip the risks immediately, which in turn is paving the way for the UK to become one of the first countries in the world to reap the benefits of AI safely.’

Sounds good so far. (Although maybe the facetious point to make here is ‘how much longer will humans ‘move just as fast’ as AI…) The paper tell us that not ‘only do we need to plan for the capabilities and uses of the AI systems we have today, but we must also prepare for a near future where the most powerful systems are broadly accessible and significantly more capable.’

We are then told the UK is spending more than any other country on AI safety - but does it matter whether we spend the most at this moment in time or does it matter whether it is the right amount to be spend, i.e., because x amount needs to be spent to keep us safe? If France goes and spends 5x more than us on their AI safety plans, would we seek to match them? Or exceed them? Is the only metric that matters the crude amount (I’d argue it shouldn’t be)?

‘Agile’ Regulation and Legacy Regulators

The Government plans to use legacy regulators such as the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), The Information Commissioners Office (ICO), and the (slightly more random) Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem), and equip them with ‘£10 million to jumpstart [their regulatory] AI capabilities'.’ It seems like a good idea to utilise the institutional knowledge of regulations over time and seems to me like a good idea at face value. It may be faster, but in the spirit of Smithian specialisation, will these regulatory bodies be able to up-skill quick enough in their knowledge of AI?

As a precursor, I do not think GTP-4 right now poses a significant risk to us. But I do think it possible that through scaling to GPT-5, 6, 7, etc, that we may see the kind of advanced, powerful and general AI that may begin to pose significant risks to the world. So I am glad that this part of the UK’s response seems to follow a similar sentiment, by making clear that: ‘the UK will continue to respond to risks proportionately and effectively, striving to lead thinking on AI in the years to come.’

However, a bit further down they explain that they ‘are going to take our time to get this right – we will legislate when we are confident that it is the right thing to do.’ I hope that a future powerful AI does not create too much harm to too many people before they become confident the time is right. How is the Government going to quantify when the time is right? I would like to see some more thinking from them on this going into 2024.

Further down they explain that an AI ‘model designed for drug discovery could potentially be accessed maliciously to create harmful compounds’ - when will the Government decide when to regulate that? Ex-post might be too late, despite the recent findings by RAND and OpenAI on bioweapons and LLMs. (Gary Marcus is suspicious of OpenAI’s methodology here though.)

On biological threats in particular, the paper assures us that the Government’s ‘2023 refreshed Biological Security Strategy will ensure that by 2030 the UK is resilient to a spectrum of biological risks [and that the] government has identified screening of synthetic DNA as a responsible innovation policy priority for 2024.’

And so, if ‘agile’ regulation means legislation that can be ramped up quickly when significant risks arise? Then this seems positive. However, if agile means ‘easy for big labs to not think about risks because the rules are lax?’ Then this is less good. I hope the former proves to be the way the UK”s agile approach heads.

The AI Safety Institute and Evals

The Government does ‘not fully understand what the most powerful systems are capable of and we urgently need to plug that gap.’ They task that to the new(ish) AI Safety Institute (AISI).

I am glad the AISI is focussed on technical AI safety and evals (which are technical means of evaluating a model’s capabilities). Now the sticking point is creating evals that are actually effective and can also deal with how you plan for post-deployment capabilities not seen whilst the model is in the lab.

And how will the Government make sure a warning from the AISI about a model’s potentially dangerous capabilities are given the correct weight needed (pardon the pun)? And the commercial lab doesn’t just try and proceed anyway if the AISI raises concerns about a model?

Because here the paper makes clear that the ‘goal of the Institute’s evaluations will not be to designate any particular AI system as “safe”.’ Does the government lessen the potentially effective bite of its AISI by saying that? Or are they being sensible because we do not even really know how to do a fully effective eval yet?

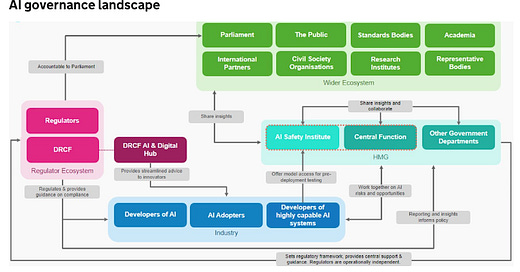

We have in the ‘AI governance landscape’ table below an arrow that demonstrates how Industry ‘developers of highly capable AI systems’ (such as GPT-4, Claude 2, LLama-2, etc) must ‘offer model access for pre-deployment testing.’

But the table says nothing about the type of access. As Apollo Research et al showed, how do we also make sure the AISI gets full white-box access, not just black-box? Black-box access means a lot of potentially dangerous capabilities cannot even be elicited as they have that little information with which to do a comprehensive evaluation of the model. White-box access gives would-be evaluators access to everything they would need for a full evaluation.

And the Government seems to agree here, when they write that, ‘if the exponential growth of AI capabilities continues, and if – as we think could be the case – voluntary measures are deemed incommensurate to the risk, countries will want some binding measures to keep the public safe.’

On Risks from AI

The Government is supposedly ‘committed to strengthening the integrity of elections to ensure that our democracy remains secure, modern, transparent, and fair. AI has the potential to increase the reach of actors spreading disinformation online, target new audiences more effectively, and generate new types of content that are more difficult to detect.’ And that ‘AI capabilities may be used maliciously, for example, to perform cyberattacks or design weapons.’

On future highly autonomous AI models such as AGI or ASI. The paper says some ‘experts are concerned that, as AI systems become more capable across a wider range of tasks, humans will increasingly rely on AI to make important decisions. Some also believe that, in the future, agentic AI systems may have the capabilities to actively reduce human control and increase their own influence.’ To which they point to the fact that the AISI is already testing for these abilities.